The words “provide for the common defense and general welfare” rank among the most abused phrases in the Constitution. I often refer to this as the “anything and everything clause.”

Partisans on both the political left and right use “general welfare and common defense” to justify all kinds of federal actions, from wars to social welfare programs. Federal supremacists take the words quite literally, arguing that they authorize the federal government to do absolutely anything, as long as it furthers the general welfare or provides for the common defense – however broadly they may define those words.

But this view unravels the entire constitutional structure.

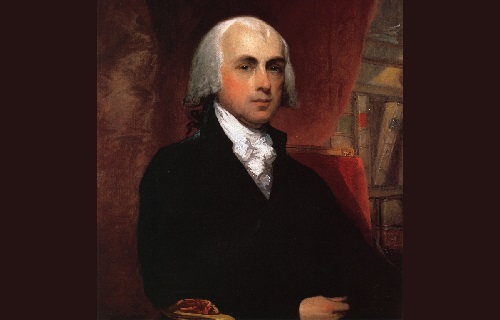

Time after time during the ratification process, supporters of the Constitution swore it created a government with limited powers. How can a government possessing the authority to take any action for the general welfare and common defense be considered “limited” in any sense? As James Madison put it in a letter to Edmund Pendleton dated Jan. 21, 1792 , he considered this expansive view of providing for the common defense “as subverting the fundamental and characteristic principle of the Government, as contrary to the true & fair, as well as the received construction, and as bidding defiance to the sense in which the Constitution is known to have been proposed, advocated and adopted.”

Madison asserted that the phrase “provide for the common defense and general welfare” was copied from the Articles of Confederation, and we find its meaning there. Madison expanded on this idea in his Report of 1800.

The Report of 1800 was a lengthy defense of the Virginia Resolutions of 1798 that asserted states “have the right, and are in duty bound to interpose” when the federal government engages in a deliberate, palpable, and dangerous exercise of undelegated powers. The resolutions were in response to the Alien and Sedition Acts. Supporters of this expansion of federal power often justified it with an appeal to the the common defense and general welfare clause. In the follow passage, Madison totally obliterates this view.

The other questions presenting themselves, are—1. Whether indications have appeared of a design to expound certain general phrases copied from the “articles of confederation,” so as to destroy the effect of the particular enumeration explaining and limiting their meaning…

In the “articles of confederation” the phrases are used as follows, in article VIII. “All charges of war, and all other expences that shall be incurred for the common defence and general welfare, and allowed by the United States in Congress assembled, shall be defrayed out of a common treasury, which shall be supplied by the several states, in proportion to the value of all land within each state, granted to or surveyed for any person, as such land and the buildings and improvements thereon shall be estimated, according to such mode as the United States in Congress assembled, shall from time to time direct and appoint.”

In the existing constitution, they make the following part of section 8. “The Congress shall have power, to lay and collect taxes, duties, imposts and excises to pay the debts, and provide for the common defence and general welfare of the United States.”

This similarity in the use of these phrases in the two great federal charters, might well be considered, as rendering their meaning less liable to be misconstrued in the latter; because it will scarcely be said that in the former they were ever understood to be either a general grant of power, or to authorize the requisition or application of money by the old Congress to the common defence and general welfare, except in the cases afterwards enumerated which explained and limited their meaning; and if such was the limited meaning attached to these phrases in the very instrument revised and remodelled by the present constitution, it can never be supposed that when copied into this constitution, a different meaning ought to be attached to them.

That notwithstanding this remarkable security against misconstruction, a design has been indicated to expound these phrases in the Constitution so as to destroy the effect of the particular enumeration of powers by which it explains and limits them, must have fallen under the observation of those who have attended to the course of public transactions. Not to multiply proofs on this subject, it will suffice to refer to the debates of the Federal Legislature in which arguments have on different occasions been drawn, with apparent effect from these phrases in their indefinite meaning…

Now whether the phrases in question be construed to authorise every measure relating to the common defence and general welfare, as contended by some; or every measure only in which there might be an application of money, as suggested by the caution of others, the effect must substantially be the same, in destroying the import and force of the particular enumeration of powers, which follow these general phrases in the Constitution. For it is evident that there is not a single power whatever, which may not have some reference to the common defence, or the general welfare; nor a power of any magnitude which in its exercise does not involve or admit an application of money. The government therefore which possesses power in either one or other of these extents, is a government without the limitations formed by a particular enumeration of powers; and consequently the meaning and effect of this particular enumeration, is destroyed by the exposition given to these general phrases.

To these indications might be added without looking farther, the official report on manufactures by the late Secretary of the Treasury, made on the 5th of December, 1791; and the report of a committee of Congress in January 1797, on the promotion of agriculture. In the first of these it is expressly contended to belong “to the discretion of the National legislature to pronounce upon the objects which concern the general welfare, and for which under that description, an appropriation of money is requisite and proper. And there seems to be no room for a doubt that whatever concerns the general interests of learning, of agriculture, of manufactures, and of commerce, are within the sphere of the national councils, as far as regards an application of money.” The latter report assumes the same latitude of power in the national councils and applies it to the encouragement of agriculture, by means of a society to be established at the seat of government. Although neither of these reports may have received the sanction of a law carrying it into effect; yet, on the other hand, the extraordinary doctrine contained in both, has passed without the slightest positive mark of disapprobation from the authority to which it was addressed.

Now whether the phrases in question be construed to authorise every measure relating to the common defence and general welfare, as contended by some; or every measure only in which there might be an application of money, as suggested by the caution of others, the effect must substantially be the same, in destroying the import and force of the particular enumeration of powers, which follow these general phrases in the Constitution. For it is evident that there is not a single power whatever, which may not have some reference to the common defence, or the general welfare; nor a power of any magnitude which in its exercise does not involve or admit an application of money. The government therefore which possesses power in either one or other of these extents, is a government without the limitations formed by a particular enumeration of powers; and consequently the meaning and effect of this particular enumeration, is destroyed by the exposition given to these general phrases.