I was originally planning on looking at the Second Amendment this week, but it occurred to me that we should examine the Bill of Rights more generally before digging into spec ific provisions.

ific provisions.

Adding a declaration of rights to the Constitution was a condition of ratification for several states, and five state ratification documents included specific proposed amendments. For instance, the Virginia ratifying instrument listed 20 proposed provisions for a bill or rights.

The most important thing to understand is that the Bill of Rights does not create rights, or give rights to anybody. It merely prohibits the federal government from taking action that infringes on preexisting rights.

Many argued that a bill or rights was necessary to place further limits on federal power. Patrick Henry chastised fellow delegates for considering a Constitution without a bill of rights during a speech at the Virginia ratifying convention on June 16, 1788, pointing out that the state constitution included a declaration of rights.

If you give up these powers, without a bill of rights, you will exhibit the most absurd thing to mankind that ever the world saw — government that has abandoned all its powers — the powers of direct taxation, the sword, and the purse. You have disposed of them to Congress, without a bill of rights — without check, limitation, or control. And still you have checks and guards; still you keep barriers — pointed where? Pointed against your weakened, prostrated, enervated state government! You have a bill of rights to defend you against the state government, which is bereaved of all power, and yet you have none against Congress, though in full and exclusive possession of all power!

But others argued a declaration of rights was unnecessary because the federal government was already restricted to its enumerated powers. Alexander Hamilton stated this case in Federalist 84, even claiming enumerating rights could pose a danger.

I go further, and affirm that bills of rights, in the sense and in the extent in which they are contended for, are not only unnecessary in the proposed constitution, but would even be dangerous. They would contain various exceptions to powers which are not granted; and on this very account, would afford a colourable pretext to claim more than were granted. For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do? Why for instance, should it be said, that the liberty of the press shall not be restrained, when no power is given by which restrictions may be imposed? I will not contend that such a provision would confer a regulating power; but it is evident that it would furnish, to men disposed to usurp, a plausible pretence for claiming that power.

Those demanding a bill of rights won the day. In fact, were it not for the promise to add a declaration of rights, several states would likely not have ratified the Constitution at all.

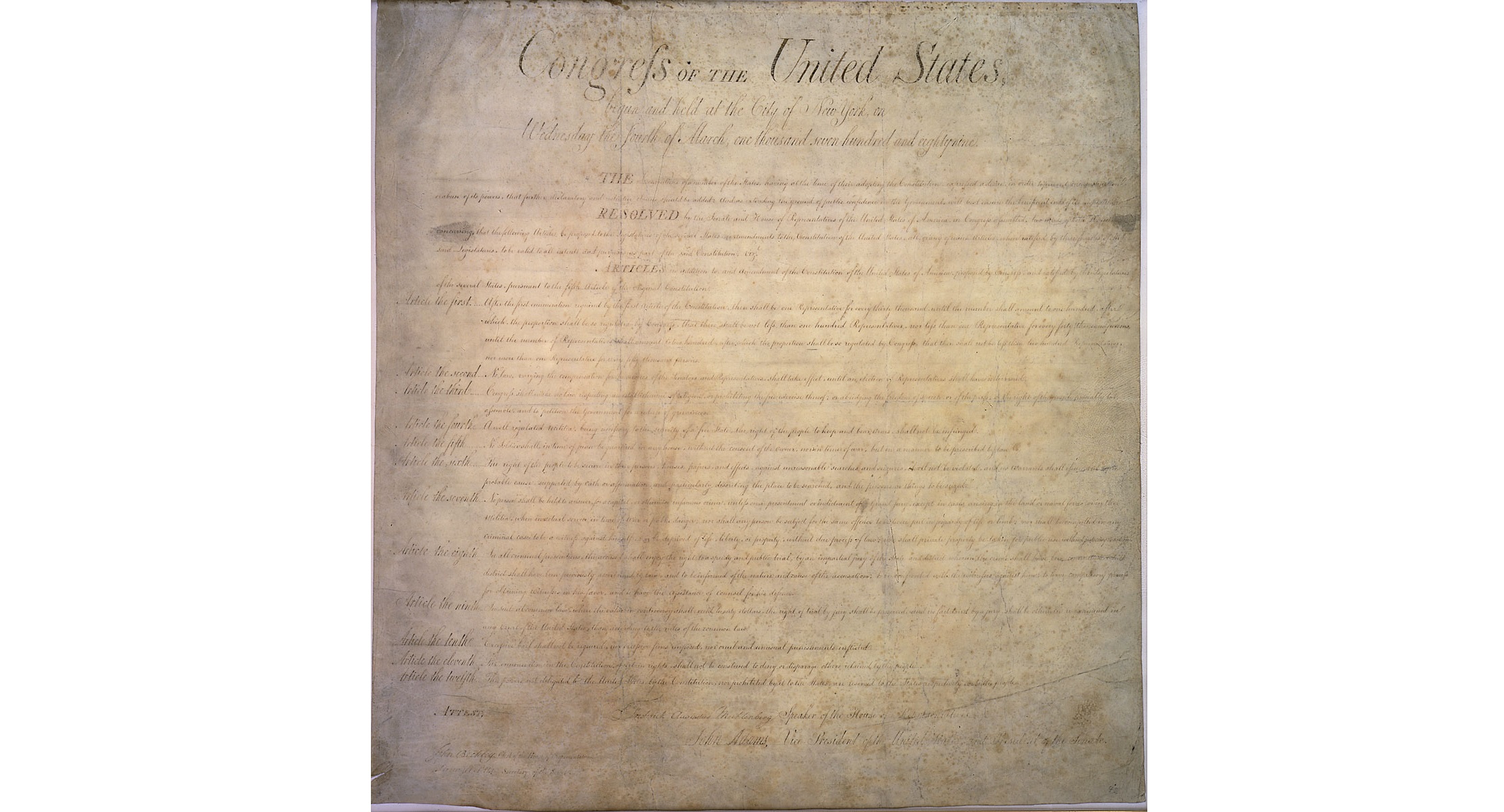

James Madison kept the promise and proposed 39 amendments to Congress on June 8, 1789. He acknowledged the arguments asserted by those who believed a bill of rights unnecessary, but appealed to the House to keep the commitment made to those who approved the Constitution with the understanding that a declaration of rights would be forthcoming, saying, “It appears to me that this House is bound by every motive of prudence, not to let the first session pass over without proposing to the State Legislatures some things to be incorporated into the constitution, that will render it as acceptable to the whole people of the United States, as it has been found acceptable to a majority of them.”

Madison went on to make it clear that a Bill of Rights was intended to further restrict the powers of the new government.

It has been said that in the federal government they are unnecessary, because the powers are enumerated, and it follows that all that are not granted by the constitution are retained: that the constitution is a bill of powers, the great residuum being the rights of the people; and therefore a bill of rights cannot be so necessary as if the residuum was thrown into the hands of the government. I admit that these arguments are not entirely without foundation; but they are not conclusive to the extent which has been supposed. It is true the powers of the general government are circumscribed; they are directed to particular objects; but even if government keeps within those limits, it has certain discretionary powers with respect to the means, which may admit of abuse to a certain extent, in the same manner as the powers of the state governments under their constitutions may to an indefinite extent; because in the constitution of the United States there is a clause granting to Congress the power to make all laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into execution all the powers vested in the government of the United States, or in any department or officer thereof; this enables them to fulfil every purpose for which the government was established.

Through debates in both the U.S. House and Senate Congress rejected some of the proposals and combined others, ultimately submitting 12 amendments to the states for consideration.

On Dec. 15, 1791, Virginia became the 11th state to ratify 10 of those amendments, crossing the required threshold to make them part of the Constitution.

Next week we will continue looking at the Bill of Rights and answer the question: were they intended to affect the states?